Thursday, Sept. 23's gorgeous weather was an excellent excuse to do something I have been itching to do for a few weeks: visit Orangeburg’s First Presbyterian Cemetery. Located downtown the small cemetery is just a short drive from SC State University where I teach.

A little harder to find was First Presbyterian Church located several blocks away. Curious to me was that the gravesite is not next to the church, hence it’s a cemetery and not a graveyard.

Ironically, there’s a large public cemetery across the street from the beautiful white church. The Presbyterian church was organized in 1835.

The cemetery opened the same year. The grounds are well kept with many large magnolia trees and other types providing nice shade in places.

My path to this cemetery began with my recent office move at SC State. Years ago, Ed Reynolds, an old friend, gave me his late father’s collection of dozens of copies of South Carolina Historical Magazine. Ed knew of my interest in history and asked me if I’d like to have the booklets. I said sure I would and picked them up at his Mt. Pleasant home.

When I was moving the books office-to-office this issue caught my eye. The SC magazine usually does not have an image on the cover but this one from October 1998 does. So I set it aside, looking forward to what someone named Elizabeth Jamison (1814-1888) from Orangeburg had to say about her and her family’s life before, during and after the Civil War.

And wow what’s story it is! I learned so much about the challenges and hardships from Mrs. Jamison’s “A Tale of the War” as she called it. (An online preview of the article can be viewed here).

The piece was edited by David J. Rutledge, an attorney in Greenville, S.C. He says he received Mrs. Jamison’s manuscript from a descendant, Mrs. Thomas W. Jamison III of Westminster, Md. who said the journal had pretty much been forgotten for a hundred years. the manuscript is published in SC historical journal in its original form except for bracketed notations, according to Rutledge.

He says Mrs. Jamison was in her 70s in the 1880s when she wrote down these memories. At the time she was living in Charleston in a small apartment at 15 Chapel St. She was barely getting by at this point late in her life. She and her family struggled greatly since the Civil War and Union Army came literally to her doorstep in 1865.

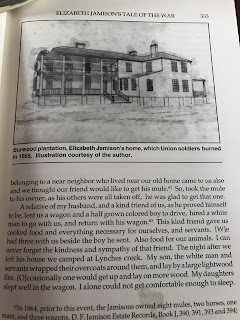

Her family home in Orangeburg near the Edisto River was burned by Sherman’s army as it marched to Columbia. The historical journal piece includes this image of the plantation house called Burwell where Elizabeth and her husband David had lived. The couple had 13 children.

Late in the war, Mrs. Jamison with some of her children (most were older and on their own by then) had evacuated Burwell sometime before when it was apparent the Union army was in the area. She did not return home until May 30, 1865 several weeks after the war had ended.

“It was very sad to see our beautiful home gone, only the chimneys and underpinning left,” she wrote. “Palings and fences all burnt...everything that could be destroyed on the property was gone.” She also suspected some neighbors and former slaves looted what may have been salvageable.

HER HUSBAND: SECESSION LEADER GEN. DAVID JAMISON

The Yankees may have been all too happy to burn Burwell. Elizabeth’s husband was David Flavel Jamison (1810-1864). He was a prominent lawyer, planter, author and state representative. He rose to general in the state militia. He is also credited as one of the founders of the South Carolina Military Academy in Charleston (the Citadel today). Jamison strongly advocated secession and was chosen to be president of the South Carolina State Secession Convention that took place in Charleston in December 1860.

Elizabeth became a widow in September 1864 when David, 53, died of yellow fever in Charleston.

TOUGH TIMES AFTER THE WAR

With the death of her husband and loss of her house as the war closed in, Elizabeth and the three or four children still with her had to rely on family, relatives, friends, and neighbors for food and shelter. Ironically, she and her children lived for a while in a former slave cabin on their plantation property.

David Rutledge notes that in her later years, Elizabeth “aided by her daughter Bessie...lived in poverty in a succession of progressively smaller apartments (in Charleston). Although Elizabeth Jamison was stripped of all that she had been born to expect (wealth, social standing, and security), she refused to become bitter or embroiled in self-pity.”

Mrs. Jamison's writings show she was a very religious woman who trusted God to not give her more than she could bear. “You know He has promised to take care of the fatherless and the widow,” Elizabeth wrote in a letter to one of her other daughters. "Dear daughter don't give up to troubles, try for the sake of the boys to be truthful and pray to bear up under all that our God thinks it best to send on you..."

Of her life and experiences, Rutledge, at the beginning of his article, wrote: "Elizabeth's tale is not unusual; her experiences were mirrored in thousands of lives all over the South. Hers is a story that began with privilege and ended in poverty. She does, however, give an uncommon view of the Civil War; her voice is that of a woman on the home front who gave her sons and husband to the war, who managed large plantations in their absence, and who inherited a new world after the conflagration was over."

CONFEDERATE GEN. MICAH JENKINS CONNECTION

Another aspect that interested me when I read the SC journal story was that one of the Jamison daughters, Caroline (1837-1902), would marry Micah Jenkins (1835-1864), who became a general in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Gen. Jenkins’ star was rising as a Confederate commander but then he was mortally wounded- accidentally shot by Southern soldiers- at the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864.

Caroline and Micah are buried together in this plot at Charleston’s Magnolia Cemetery.

Micah Jenkins graduated from what was then called the Military Academy of South Carolina (today called The Citadel). A barracks on campus is named for him.

ELIZABETH AND DAVID JAMISON'S GRAVESITES IN ORANGEBURG

Back to where this story began: Orangeburg’s Old Presbyterian Cemetery. This is where David and Elizabeth Jamison are buried. A granite obelisk marks Gen. Jamison’s grave. Under his name is inscribed “Soldier, Statesman, Scholar.” And at the bottom is “President of the Secession Convention.” The tall monument was “Erected by His Friends” says another inscription.

There is an unconfirmed story that Mrs. Jamison had her husband's remains moved as Sherman's army advanced on the area. She feared the Yankees might dig him up in order to desecrate one of the top secession leaders. (In Charleston at St. Philip's Church John C. Calhoun's casket was actually moved for the very same reason).

There is an unconfirmed story that Mrs. Jamison had her husband's remains moved as Sherman's army advanced on the area. She feared the Yankees might dig him up in order to desecrate one of the top secession leaders. (In Charleston at St. Philip's Church John C. Calhoun's casket was actually moved for the very same reason).

Mrs. Jamison’s granite die on socket stone is inscribed only with her name, Born Feb. 15, 1814, Died Dec. 11, 1888 and “Wife of David. F. Jamison.” She was 74 when she died and never remarried after losing her husband 24 years earlier.

Three young Jamison children, two who were around 1 year old, are also interred here in graves near their parents.

OTHER INTERESTING GRAVES AT ORANGEBURG’S OLD PRESBYTERIAN CEMETERY

The largest family plot at the Presbyterian cemetery belongs to the Glovers. Glover grave markers of all shapes and size, more than a dozen, are within these brick walls and fence.

The oldest (below) is the columned marker over the grave of Confederate Col. Thomas Jamison Glover (related to David Jamison no doubt). He was mortally wounded at the Second Battle of Manassas (or Bull Run) on Aug. 30, 1862. He was 33. The column is cut in an angle at the top symbolizing a life tragically cut short.

This next family plot caught my eye because of the old rusted wrench on one of the bricked foundations. I guess it’s a way to show the restoration work that was done in fairly recent times.

A soul going straight to Heaven is an interpretation of this stone’s engraved hand with a finger pointing up to the sky and afterworld. It's a not uncommon symbol that is striking in its simplicity and meaning.

The one below is a curious one. Here is buried “Our Sunshine Nellie” daughter of D.N and J.R. Smith. She died in 1901 at age 12. Under the two praying angels is this haunting epitaph: “The costly Sacrifice of Compulsory Vaccination.”

Here is another symbol-rich gravestone for another young child whose life was cut way too short. A hand holding a bouquet of roses may symbolize love and loss, purity and beauty.

Little Hattie Bull died on October 31- Halloween (was it celebrated way back then?)- in 1858. Her age, inscribed in stone, is very specific, as often was the case in the olden days: “5 Y’rs. 4 Mo’s. & 19 D’YS.”

In the dark shaded corners of this cemetery are some graves that seem lost to time.

Finally, back in the Glover family plot, is this somewhat eerie grave. The artistry is mostly floral but what is this evil looking face staring back at me?

No comments:

Post a Comment